One hundred thousand Koreans dead in a single day. The next day five hundred thousand—all dead from a strange virus, rapidly mutating with every vaccine. Rumors begin to circulate that eating the livers of little girls will cure the disease. To protect her remaining family, Dori flees with her younger sister to the barren expanse of Russia.

In unfamiliar territory, they encounter a caravan of Koreans making their way across the endless winter wasteland. Jina, a warmhearted young woman, adopts Dori and her sister into her protection, much to the disapproval of her family. Together, they carve a space for intimacy and love in a time of catastrophe.

Review and Analysis

Please be aware that there are light spoilers to major plot points ahead, and there is a content warning for rape and violence.

At their core, post-apocalyptic novels explore what humanity will do in the face of disaster. Against a dystopian backdrop, societal conventions that we take for granted are juxtaposed against extreme circumstances to see if they can withstand the moral weight we place upon them. In To The Warm Horizon, filial piety and country borders seem almost ludicrous when pillaging and murder have become commonplace survival tactics.

Without access to the internet, news, or media, the characters are thrust frantically into the unknown. The characters and the reader are left to imagine the devastating impact of the virus, and to either follow hope that a new society can be built, or to shelter in place and hope that someone else finds a cure. The characters’ core beliefs are tested when put up against worldwide chaos; whether it’s the outlandish belief that children’s livers can cure disease or a child’s flimsy belief that adults can protect them.

The book begins from the perspective of Ryu, a middle-aged woman who lost her daughter to the plague. She is caught in a marriage of obligation, never quite sure if she’s “living well.” There are moments when she longs for the familiar comforts of Korea, but she is painfully aware that their old way of life can never be recovered. Like our own global pandemic, history is marked as the “before times” and the “after times,” and the characters’ nostalgia for “Korea” is a longing for the familiarity of the past. The flaws of their past society had come to Ryu’s attention gradually, and there are moments in her narration that show she is still working through these realizations as she looks back on her life in hindsight. Above all she is worried of becoming desensitized to the brutality surrounding her, and reflects on the incessant chatter of the media that turned “real disaster into a joke.”

In the post-apocalyptic future, the void of knowledge left behind after the eradication of the Internet is felt sharply by each of the characters. Without access to the global news, the plot feels claustrophobic as the characters are trying to make sense of their circumstances seemingly in a vacuum, adding to the heightened atmosphere of Choi’s writing. The resulting difficulties in communication range from verbal to emotional. Soje expertly translates Dori and Jina’s first endearing encounter, when Jina says, “A-im peurom Koria. Wheo al yu peurom?” Aside from being surrounded by foreign tongues, there is a vague generational split which causes endless conflict in communication. The idealism of the younger characters is shown to clash with the older figures, who vary in skepticism to fatalism.

Of all the characters, Jina’s Father and Ryu’s husband Dan are the most eager to uphold the ideals of the past. For Jina’s Father, he holds steadfast to his belief that family must protect each other no matter what—that there is no such thing as good or bad when it comes to family. In one of the most chilling scenes of the book, Jina is stunned by the realization that her family is capable of horrible things:

“I looked around. My relatives were watching me. They watched me, completely wrecked and in tears. I recalled their names. Not Uncle or Auntie, but their proper names. When I matched names to faces, these people felt like strangers. I didn’t see family. We could easily betray each other. We could beat and abandon each other. We could rape and kill each other. Dad’s conviction that family would never do that to each other was as thin as Bible pages. He drove Dori out in order to protect that weak thing. I know Dad would do anything for me. Is that why he tried to beat, rape, and kill Dori? Who was that actually for? These awful questions.”

Jina’s Father is so unflinching in his perception of the world, that he is insistent upon the suffering of his daughter as a necessary sacrifice for the “new nation.” Much like those in our world who oppress others to align themselves with power, he is convinced that he can claw his way through the ranks using violence to build a better life for himself and Jina. In our world, including but not limited to Korean and other Anglo-European cultures, men often look to diminish the suffering of women and other marginalized groups as an unavoidable consequence of maintaining tradition. For Jina’s Father, a “new nation,” built on the slavery and abuse of his own daughter does not promise a future much different than the past.

In times of social upheaval, what should we strive to preserve? Each character has someone they’ve set out to protect, and through them we can see the ideals that they value most. Dori wants to protect her sister—aptly named Joy in the English translation, or “미소” for “smile” in the original Korean text—not only as family, but because Dori values genuine love and connection. Jina holds hope close to her heart; a hope in others, as well as a hope in the future. Gunji, after spending most of his teenage life beaten down and berated by those stronger than him, wants to protect others who are good and precious. Despite the hardships surrounding them, they all hold onto vivid dreams of a brighter future, just out of reach.

While Ryu starts off the novel, Dori and Jina close off the story in the only dual-perspective chapter of the book. Perhaps their voices, indistinguishable from each other, mark a hopeful future for the duo and for the other characters in the book. Like our own real-world pandemic, the ending is left ambiguous. Despite all of the unknowns, the queer affection at the conclusion feels deliberate, and leaves us with hope that there is a warmer future on the horizon.

Thoughts on the Translation

The English translation of To The Warm Horizon was written by So J. Lee, also known as Soje, a Korean translator and writer who makes a quarterly e-zine featuring a Korean poem and multiple English translations. As a translator, they are particularly sensitive to gendered pronouns, as shown through an essay that they wrote in 2020 entitled “Not Exactly a Sister.” Soje’s expertise in the source culture and Korean queer fiction is indispensable as the translation is enriched with the translator’s own proximity to the themes and Korean identity. While successful translations can be achieved by scholars and writers of any ethnicity, there is a tender familiarity to Korean sensibilities without any embellishment that may be found in other popular translated Korean works. Somehow it makes the writing feel more genuine, knowing that the translator is deeply aware of the nuances of Korean writing and current societal issues. Personally, I am thrilled that a Korean writer is giving so much attention to gender and queer issues in Korean literature, and I will eagerly look for more of Soje’s work in the future.

Conclusion

To The Warm Horizon is compelling because of the uniquely Korean take on pandemic literature and because it places queer Korean women at the forefront of its plot. It’s valuable to have narratives told by queer women on their own experiences with love, abuse, and overcoming adversity. Choi Jin-Young allows many of her characters to narrate their own chapters, allowing their individual identities to be interwoven into the plot, without exotification or fixation. Jina and Dori’s queerness, Jina’s mixed-race background, and Joy’s deafness are never reduced to pretentious plot points, nor does the author weigh down the novel with justifications of their identities. Instead, they are genuine young people trying to survive in a world that was not made for them.

Writing ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Plot ⭐⭐⭐

Themes ⭐⭐⭐⭐

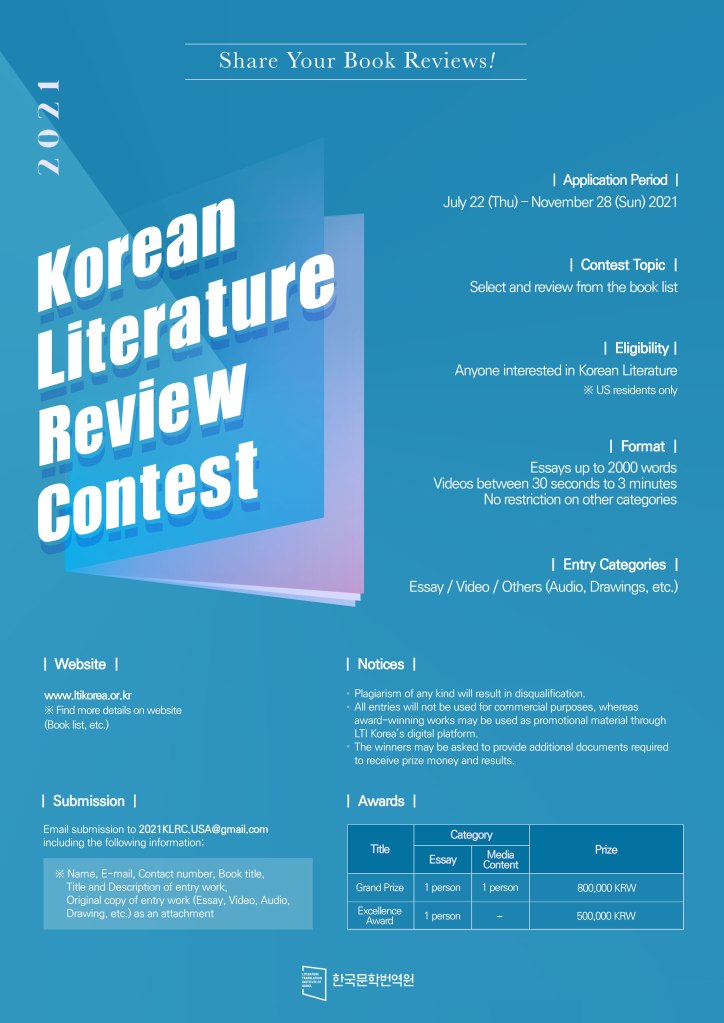

This review was written as a part of the Korean Literature Review Contest supported through the Literature Translation Institute of Korea. (#Review_K_Literature!) You can find more information on the contest on the KLRC’s Instagram or on their website.

Leave a comment