This summer was for memoirs by the likes of Dolly Alderton, Baek Sehee, and Jennette McCurdy. What can we learn from other women’s vulnerability, and how can our relationships with women change us?

Back in May, I surprised my life partner, Camila, with a visit to Chicago. My other partner, Ike, picked me up from O’Hare and hid me in their trunk (openly connected to the back seat, don’t worry). With the help of our friend Dani, we spun an elaborate ruse about a Cubs game to get Camila to clear her evening schedule. Ike and I recorded the whole affair: her getting into Ike’s car, me popping up from the back trunk, and her look of disbelief as she registered that I was not in London as I should’ve been. The week was filled with more of our day-to-day love—cooking together, visiting her at work, going to the lake, and generally basking in the sunshine of Chicago in the early summer.

On one of our evening walks, Camila was excitedly telling Ike and me about a book she was reading called Everything I Know About Love by Dolly Alderton. Camila loves to collect quotes like fabrics for a quilt—she weaves the words of others to curate a pastiche of language to describe her own feelings. It’s one of my favorite things about her! Anyway, she read this particular excerpt to us that day, a conversation between Dolly and her childhood best friend, Farly:

“I want to know what that feels like, to be truly committed to someone, rather than having one foot out the door.”

“You’re too hard on yourself,” she said. “You can do long-term love. You’ve done it better than anyone I know.”

“How? My longest relationship was two years and that was over when I was twenty-four.”

“I’m talking about you and me,” she said.

The day after I arrived back at Heathrow, I walked to my favorite Waterstones on Gower Street and picked up a copy of Everything I Know About Love. When I approached the till, the employee gushed, “Oh, I loved this book! Have you seen the BBC series?”

“I haven’t yet! My friend rated this five stars, and I knew I had to read it.”

“I completely agree, it’s an amazing read!”

(Honestly, nothing makes me feel as good as when the workers at a bookstore rave about the book I’m buying. It always makes me feel like I’ve been invited to sit with the cool kids at lunch.)

Over the next few days, I devoured Dolly’s memoir. As promised by Camila and the Waterstones employee, it was an absolute page-turner. The way Dolly writes so candidly makes you feel like you know her intimately. I saw myself in her, and I saw whispers of other women I know in her. She is witty, obsessive, feeling, and ultimately trying her best.

Is it a feminist book? To be honest, I don’t think it really matters. I don’t believe every woman’s personal narrative needs to be co-opted into a grand political message other than radical self-inquiry and loving of oneself and other women. For me, there can be feminism in that simplicity, but I don’t think it’s a necessary qualifier. These days the “Messy Woman” has become a bit of a trope in shows and literature. (Read: How Messy Millennial Woman became TV’s most tedious trope)

As a previously self-proclaimed Serious Goose™ who is now a (charmingly scatterbrained) Silly Goose™, I deeply relate to the liberation from perfection that the “Messy Woman” trope carries. However, I believe the so-called “mess” inherent to our path of self-discovery should be regarded with fondness rather than a weakness of gender.

In Everything I Know About Love, Dolly talks about her journey with therapy. The relationship Dolly had with her therapist, Eleanor, had the familiar tones of harsh self-examination for the purpose of healing and developing a steadier sense of self. After finishing Dolly’s memoir, I finally felt compelled to pick up I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Sehee, translated by Anton Hur.

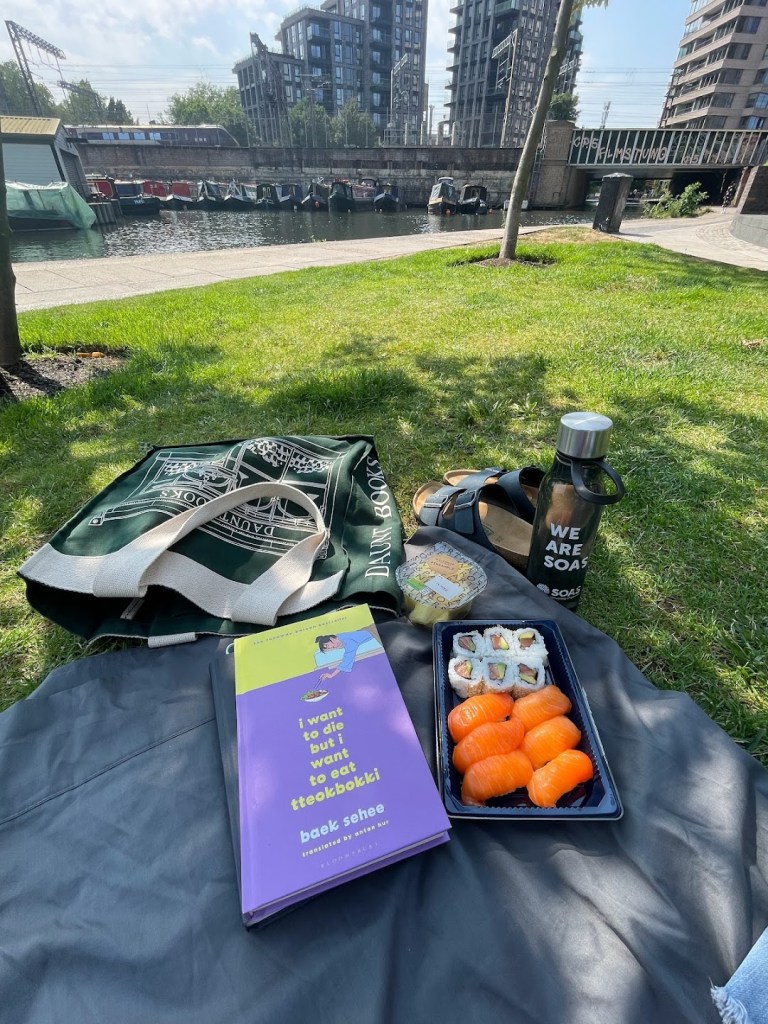

I remember being in Korea and watching I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki climb up the bestsellers shelf at the Kyobo in Gwanghwamun. I was enamored with the cute cover and the punchy title, but regrettably didn’t speak enough Korean to make it an easy read. (Shoutout to translators, bless.) The memoir is quite literally a transcription of the author’s sessions with her psychiatrist, interspersed with personal essays on topics ranging from mental health, relationships, her dogs, and her family.

It sounds like a gimmick, but reading a transcription of someone’s verbatim (albeit translated) conversations with their therapist felt voyeuristic—similar to how it feels morally gray to eavesdrop on gossip at a cafe or to rubber-neck as you drive past an accident on the highway. However, the author precedes her transcripts with this:

“Why are we so bad at being honest about our feelings? Is it because we’re so exhausted from living that we don’t have the time to share them? I had an urge to find others who felt the way I did. So I decided, instead of aimlessly wandering in search of these others, to be the person they could look for—to hold my hand up high and shout, I’m right here, hoping that someone would see me waving, recognize themselves in me and approach me, so we could find comfort in each other’s existence.”

As a person who habitually over-shares, I found so much value in reading Sehee’s conversations with her therapist; Not just to satiate my morbid fascination with strangers’ lives, but also to observe her psychiatrist’s evenhanded untangling of Sehee’s mental knots. The book motivated me to devote the same care to the messes in my own life.

The last memoir I read this summer was Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died. As one of last year’s hottest library loans, wait times on Libby were months long—but I finally managed to get the audiobook narrated by Jennette herself. Another memorable title, Jennette writes about her toxic relationship with her mother and how she coerced Jennette to become a child actor.

Perhaps it’s the iCarly nostalgia or my recurring obsession with celebrity culture, but I thought this memoir was worth all the hype it received. Like Everything I Know About Love and I Want To Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, I finished Jennette’s memoir in less than two days because I was so enthralled with her narrative prowess. Where Dolly’s memoir illustrated the transformative power of tenderness between women, Jennette’s memoir deconstructed the generational impact of women hurting other women. Jennette writes:

“Maybe I feel this way now because I viewed my mom that way for so long. I had her up on a pedestal, and I know how detrimental that pedestal was to my well-being and life. That pedestal kept me stuck, emotionally stunted, living in fear, dependent, in a near constant state of emotional pain and without the tools to even identify that pain let alone deal with it. My mom didn’t deserve her pedestal. She was a narcissist. She refused to admit she had any problems, despite how destructive those problems were to our entire family.”

Originally a one-woman show, Jennette has masterfully constructed her memoir to exhibit her wit and vulnerability. Tied with the fierce worldwide success of the Barbie movie, it seems like women are entering a new era of collective femininity rooted in reflection and sensitivity as a virtue. In all of the memoirs I read this summer, the authors’ voices are distinct and empathetic, and they all remind me of the TikTok sound from Anne with an E—“How I love being a woman!” And if being a woman is messy side tables, intimate friendships, crying in therapy sessions, and healing self-examination, I hope more women can benefit from sharing and engaging with memoirs like these.

Leave a comment